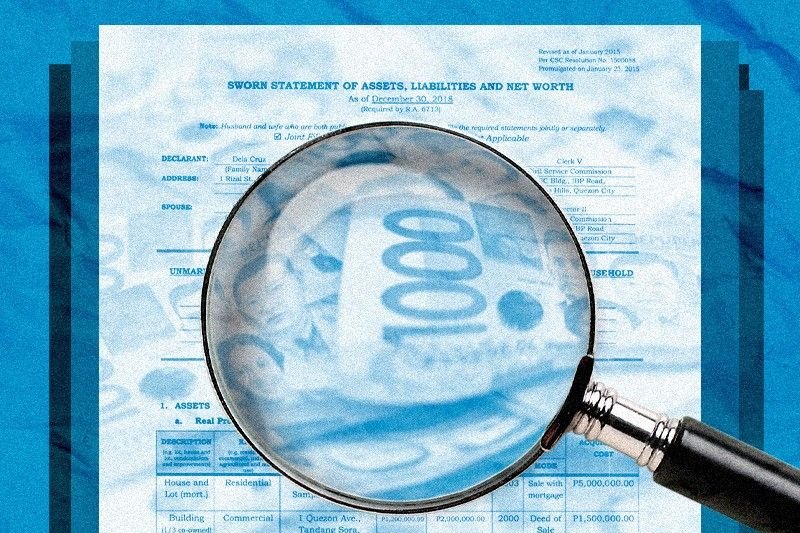

MANILA, Philippines — The Statement of Assets, Liabilities and Net Worth (SALN) is supposed to help the government and citizens keep track of a public official’s wealth. Yet even as more lawmakers put theirs on public record amid corruption probes, questions remain over whether these declarations are in any way accurate.

But first, what exactly goes into a SALN?

Filing a SALN is a constitutional requirement for public officials, intended as a tool for transparency and a safeguard against corruption and unexplained wealth.

Beyond basic details like name, spouse and government position, a SALN should provide a truthful record of an official’s assets. This includes real and personal property, financial obligations or debts, business interests and financial ties, as well as any relatives holding positions in government.

An official’s net worth is then determined by combining the value of real property and personal assets, including cash and other valuables and deducting any liabilities.

In essence, officials simply list under oath how much they own and what they owe without having to submit supporting documents.

Verification of SALNs largely depends on government action. Without such oversight — and without making the records public — officials’ wealth stays out of sight.

This only demonstrates how much a SALN filing first hinges on a government official’s honesty, according to Paolo Tamase, associate dean of the University of the Philippines College of Law.

Because of this honesty, global tax expert Mon Abrea told Philstar.com that it is possible for public officials to underdeclare assets or overstate debts to make their wealth appear smaller.

With accountability primarily reliant on government action to verify SALNs, such a tool is not foolproof.

The ‘loopholes’

Tamase and Abrea told Philstar.com that, historically, loopholes have allowed officials to sidestep public and government scrutiny of their finances.

Offshore accounts, cash or art conversions, and the use of dummies or corporate layers are just some of the methods that public officials have used to keep their wealth hard to track.

When officials store funds abroad, Tamase said it becomes difficult for authorities to trace and verify. Converting wealth into cash or assets without official records, like art, further complicates the process.

Dummies is another tactic, where officials register properties or companies under another person’s name, like their relatives or business associates, to understate any assets, Abrea said.

Corporate layering compounds this, creating complex ownership structures that make it difficult to identify the real owner.

“Despite these loopholes, there are many tools at the disposal of our government to verify if a public officer is lying in his SALN, which is a criminal offense,” Tamase said.

Why SALNs should be publicized

While it may look like a simple form, a SALN is still a sworn statement that can land a public official in court. Being notarized, it affirms that all information provided is true, and any falsification or omission can lead to administrative and criminal charges.

Corporate lawyer and litigator Dino de Leon explained that it is the public officials’ responsibility to justify their declared wealth, especially when it doesn’t match their official salary.

“Further, the wealth that they do not disclose may be argued to be presumably ill-gotten and the onus is on them to prove otherwise,” he told Philstar.com in a message.

Even though supporting documents are not required when filing the SALN, public officials may be called upon to submit proof should discrepancies arise.

By signing the SALN, Abrea said, officials grant the Ombudsman legal access to also review financial records, such as tax filings and property registries, to deter falsification and misrepresentation.

He stressed that for SALNs to become an effective anti-corruption tool, the Ombudsman and Bureau of Internal Revenue must strengthen lifestyle checks, improve data-matching systems and impose appropriate penalties.

If authorities find irregularities, officials can face charges ranging from falsification and perjury to graft and plunder.

With millions of government officials submitting SALNs, however, Tamase said cross-checking each one is no walk in the park. That’s why ensuring public access to such documents is crucial.

It not only adds pressure to the government to avoid taking part in corrupt practices but also lets citizens monitor the lifestyles of those elected or appointed.

“No tool is perfect, but for all its faults, they are an effective way of shedding light on the wealth of public officers, especially if they are disclosed to the public,” Tamase said.

The Office of the Ombudsman only recently restored public access to government officials’ SALNs, reversing a Duterte-era policy that had restricted the public and media from obtaining copies except under strict conditions.

Progressive groups and lawmakers welcomed the move, calling it a step toward holding those in power accountable amid a multi-billion-peso corruption scandal allegedly reaching the highest levels of government.